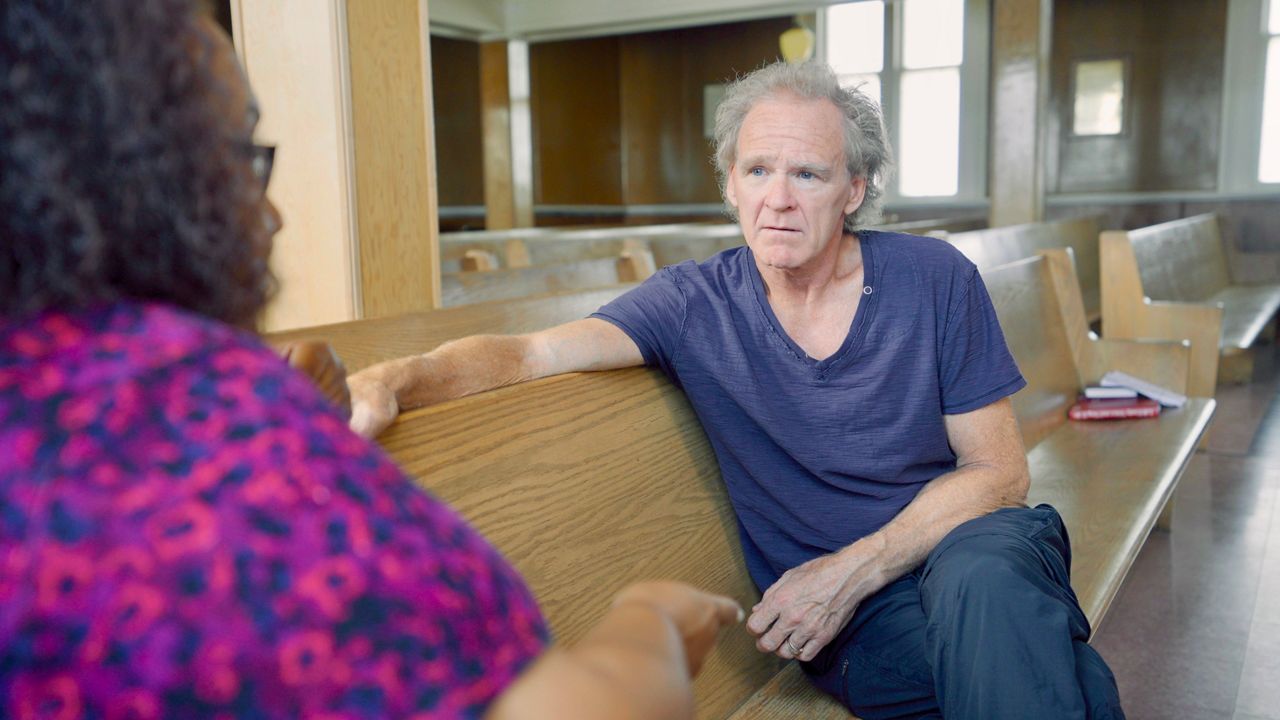

POMONA, Calif. — Ray Adamyk calls it a “God moment.”

Inspired by the Black Lives Matter movement and racial injustice in the Black community, Adamyk was looking for ways to contribute to the cause when he found an old church in his hometown of St. Catharines, Ontario, Canada, with a long and storied history.

The Salem Chapel is one of the oldest Black churches in St. Catharines, Ontario — about 15 miles northwest of the U.S.-Canada border. The church is where abolitionist Harriet Tubman worshipped and organized U.S. anti-slavery efforts. St. Catharines was the last stop of the Underground Railroad, historians say.

“I grew up in this little town of St. Catharines, and I didn’t know anything about [Harriet Tubman’s connection to the area],” said Adamyk, who now lives in Claremont. “I went to school here. They didn’t teach us anything about it. I can’t believe it. I used to live across the street from this chapel. And my boxing club was on the other side of the street.”

“This is where Harriet Tubman brought all of these African American Canadian refugees,” said Adamyk.

So when Adamyk called up Salem Chapel last year to see how he could help, he reached Rochelle Bush, the church’s trustee. Bush told him of the building’s dilapidated state.

“She said people come from all over the world to see it, but it’s falling apart. It needs historic restoration,” said Adamyk, recalling his conversation with Bush.

The 250-seat Salem Chapel British Methodist Episcopal Church, formerly the Bethel Chapel African Methodist Episcopal Church, was built nearly 170 years ago but had fallen into disrepair.

And it seemed fitting or just a sheer coincidence that Adamyk, the president of Pomona-based Spectra Co., specializes in fixing old historic buildings. His company has helped restore historical landmarks such as the El Capitan and Pantages Theatre in Hollywood, and the Millennium Biltmore in downtown Los Angeles.

Fixing up Salem Chapel was life coming full circle for Adamyk.

“When I told her that my company does historic restoration, she started to cry,” said Adamyk. “She was saying I have been crying for [someone to help] for 25 years.”

Bush told Spectrum News she was initially skeptical of Adamyk and his offer to renovate the church. He wasn’t the first to promise to fix up the old church.

“We’re going to come and do it,” said Adamyk.

“This was providential,” he added of the chance meeting. “It was very special and unique. A God moment.”

As the legend goes, St. Catharines, Ontario, Canada — about 15 miles from Niagara falls — served as the last stop of abolitionist Harriet Tubman’s clandestine Underground Railroad.

Born Araminta Ross, Harriet Tubman (who later took her mother’s first name Harriet and married John Tubman) was born enslaved on a Maryland plantation in 1820.

In 1849, Tubman escaped slavery and soon began helping others.

Tubman, better known as the Moses of her people and Underground Railroad conductor, had a network of safe houses or depots, as historians called it, to hide runaway enslaved African Americans in the northern part of the U.S.

When the U.S. passed the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act, she and other African Americans fled north to Canada. The British Empire, which controlled Canada, abolished slavery in 1834.

The U.S. Fugitive Slave Act made it legal for bounty hunters and other slave catchers to recapture enslaved African Americans who fled the South and return them to their owners for a hefty reward. The act also allowed people to suspect and kidnap African Americans living in the free north and accuse them of being runaway slaves.

“It was no longer safe to be in the North, so thousands of Black people, including Harriet Tubman, relocated to Canada,” said Bush, the Salem Chapel trustee and resident historian. “Tubman extended her Underground Railroad to Canada. She set up her base of operations here at St. Catherines. This place was a way for her to secure her freedom and the safety and freedom of thousands of others.”

“From here, she would go back and forth,” said Bush, whose great-great-grandfather Reverend James Henry Harper served as one of the church’s minister when Tubman was a member.

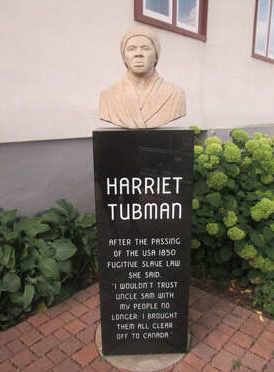

After the passing of the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act, Tubman reportedly said: “I wouldn’t trust Uncle Sam with my people no longer; I brought them all clear off to Canada.”

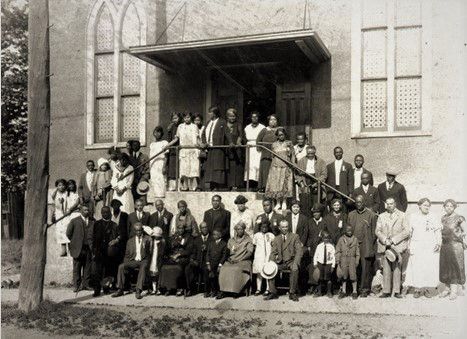

The formerly enslaved people from the South built the Salem Chapel (known then as Bethel Chapel AME Church) in the early 1853 and opened in 1855. Those formerly enslaved people designed the church with gothic windows and architecture, similar to Baptist churches in the South.

At St. Catherines, the church was the center of what residents called at the time “the color village” because of the number of free African Americans that settled there, said Bush.

She said in its heydays, over 190 people would fill the pews and worship at the church.

The church served as Tubman’s place of worship and organize U.S. anti-slavery efforts and rescue operations.

Tubman and her parents lived in St. Catherines in a quaint house on North Street, beginning in 1851. She left Canada for Auburn, New York, in 1859, where she continued to fight against slavery in the U.S., joining the Civil War as a nurse and spy and even led a major military operation.

Tubman died of pneumonia at 93 in 1913.

Over the years, the Salem Chapel fell into disrepair. Membership dropped.

Despite being listed as a national and provincial historic site, few worshippers sit in the pews anymore. There are only seven active members, said Bush.

“It’s a forgotten treasure in African American history,” she said.

What helped financially sustain the church were the few mostly older African American tourists who would make a pilgrimage to the Salem Chapel. Bush, who owns and operates Tubman Tours Canada, which specializes in narrated underground railroad tours of the Niagara-Ontario region, said the Salem Chapel averaged 4,000 to 5,000 tourists a year pre-COVID.

The museum is throughout the church. Pictures of Tubman and other freedom seekers adorn the walls. It’s about $5 U.S. dollars to get in.

“They’d come here and sit on the original pews that Tubman and other freedom seekers sat on and touch the original pulpit,” she said. “Some cry. Sometimes they just need that moment for themselves.”

The coronavirus pandemic further exacerbated their dire financial situation.

“We had nobody,” said Bush. “We had no additional income. Some of the money we saved for restoration we had to use, but fortunately, our overhead is low.”

A few years ago, Bush set up a GoFundMe in 2017 to help renovate the church.

Over the years, the cold Canadian weather and the church’s location in a high traffic area where cars rumble and whoosh by have shaken and deteriorated the nearly 170-year-old building.

Bush said the front door awning and the window sills needed to be replaced.

The roof gable, lower-level windows, and the gallery and sanctuary floors all need work.

The front windows and awning have been repaired but there’s more work to be done, said Bush.

Last year, a bust of Harriet Tubman on the church’s grounds was vandalized and destroyed.

“The Salem Chapel is a crown jewel,” said Bush. “It needs to be restored.”

The GoFundMe to restore the church raised $100,000. The Canadian government also pitched in another $100,000 through the federal Supporting Black Canadian Communities Initiative.

Adamyk, the developer, is contributing an additional $200,000 in services to fix up the building.

Adamyk visited the church last year and was overcome with emotion.

“I fell to my knees and said a prayer,” said Adamyk. “It was such a special moment knowing that Harriet Tubman was there.”

From his experience restoring old buildings, he said the church needed about $3 million to be fully restored.

“It’s dilapidated,” he said. “There are so many parts missing. The wood trim and all the windows need replacing. The paint is falling off outside and inside. There are some plumbing issues, structural issues, and roofing issues.”

But there is beauty inside those walls, he added. He’s shot video of the Salem Chapel to help raise awareness about the importance of restoring the old church.

Because of the coronavirus pandemic, he expects to begin work in 2023.

Adamyk is working with Pomona city leaders to raise additional funds for the church by hosting a Unity Walk on July 4 in Pomona. Adamyk said the 1.5-mile walk would start at Lincoln Park and end at the Pomona Fairplex. City leaders will unveil a new Harriet Tubman statue in Lincoln Park.

All proceeds from Unity Day LA will go toward the restoration of Salem Chapel, he said. Adamyk has also started a new GoFundMe to raise more money to restore the church.

“This is about preserving the legacy of Harriet Tubman,” he said. “We think of the Lincoln Memorial or the Washington Monument, and we would never let it fall in disrepair. But here we are. This [church] is part of Black history. It’s a historic landmark.”

“We’re here to preserve her legacy,” he added. “She was Moses of our generation. She saved hundreds, thousands of people who were going to die in slavery. She’s my hero.”