This story is the first installment of our three-part series on the country’s diabetes epidemic.

CLEVELAND, MISS. – The waiting room at Cardiovascular Solutions of Central Mississippi is simple, yet inviting, and always busy. Some patients have driven two hours for their appointment with the doctor. Most people around here just call him Doc — the name Foluso Fakorede doesn’t roll easily off the tongues of those with the honeyed southern accents of the Mississippi Delta.

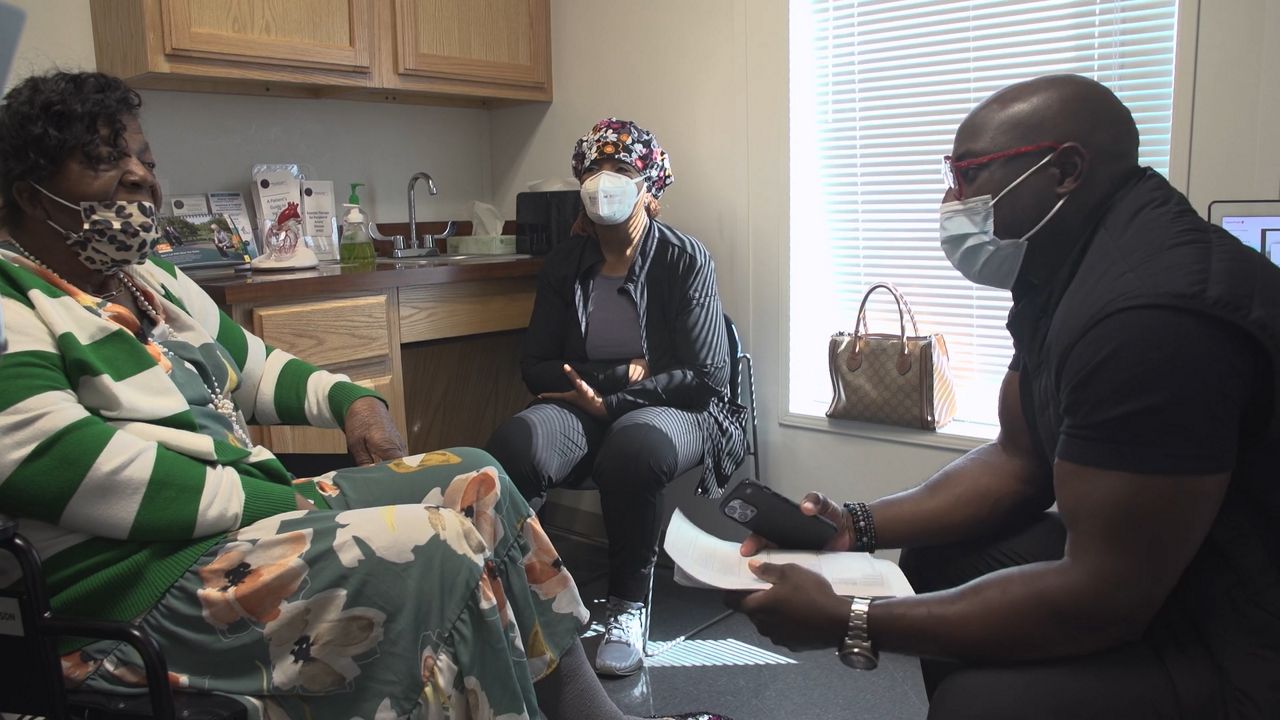

When Fakorede enters an exam room, he greets each patient formally — manners are important around here — but then he pulls up a chair, leans in, and speaks to them like family.

“Watch your sugars. Watch what you eat. You gotta eat the right things now, mama,” Fakorede reminds one patient.

“No sugary drinks. That sweet tea, you gotta cut it out,” he tells another.

The man looks incredulous.

Variations on this same conversation play out many times a day in Fakorede’s clinic. A large portion of his patients have diabetes or are pre-diabetic. “We live in a country where diabetes and obesity are our biggest health challenges,” he explains.

He’s not wrong. The Centers for Disease Control estimates about 37 million Americans have diabetes, and another 96 million are pre-diabetic. Here in Mississippi, the diabetes rate is even higher than the national average — close to 15% of the adult population.

“There are a lot of patients who actually walk into this clinic who do not realize they're a diabetic until I draw their labs,” says Fakorede.

Podcast

Erin Billups joined Spectrum News NY1's Errol Louis' podcast "You Decide with Errol Louis" to discuss their new collaborative special report “USA1C: Fighting the Rise of Diabetes,” which is currently airing on Spectrum News nationally.

Dr. Fakorede, an interventional cardiologist, moved to Mississippi in 2015. Since then, he has dedicated himself to preventing one of the most shocking and preventable outcomes of uncontrolled diabetes — lower limb amputation.

“Everyone knows that their grandmother underwent an amputation because of her poor sugar,” he explains. “But what caused that whole clinical trajectory to happen?”

The cause is a condition called peripheral artery disease — or PAD — which leads to the buildup of fatty plaque in the arteries, restricting blood flow to the legs. The risk of developing it is 50% greater in Black Americans than in white.

It is a consequence of uncontrolled blood sugar levels. Without proper blood flow, wounds may not heal, particularly on toes.

“That's why we in medicine see a high rate of amputations, because they feel that taking off that toe or that infected foot is the ultimate solution,” explains Fakorede. The problem with that strategy, he says, is that it doesn't address the lack of blood flow that led to the infection, leaving patients at risk of further PAD complications in the future.

“After an amputation, 30% of them will have another amputation of the other limb,” says Fakorede.

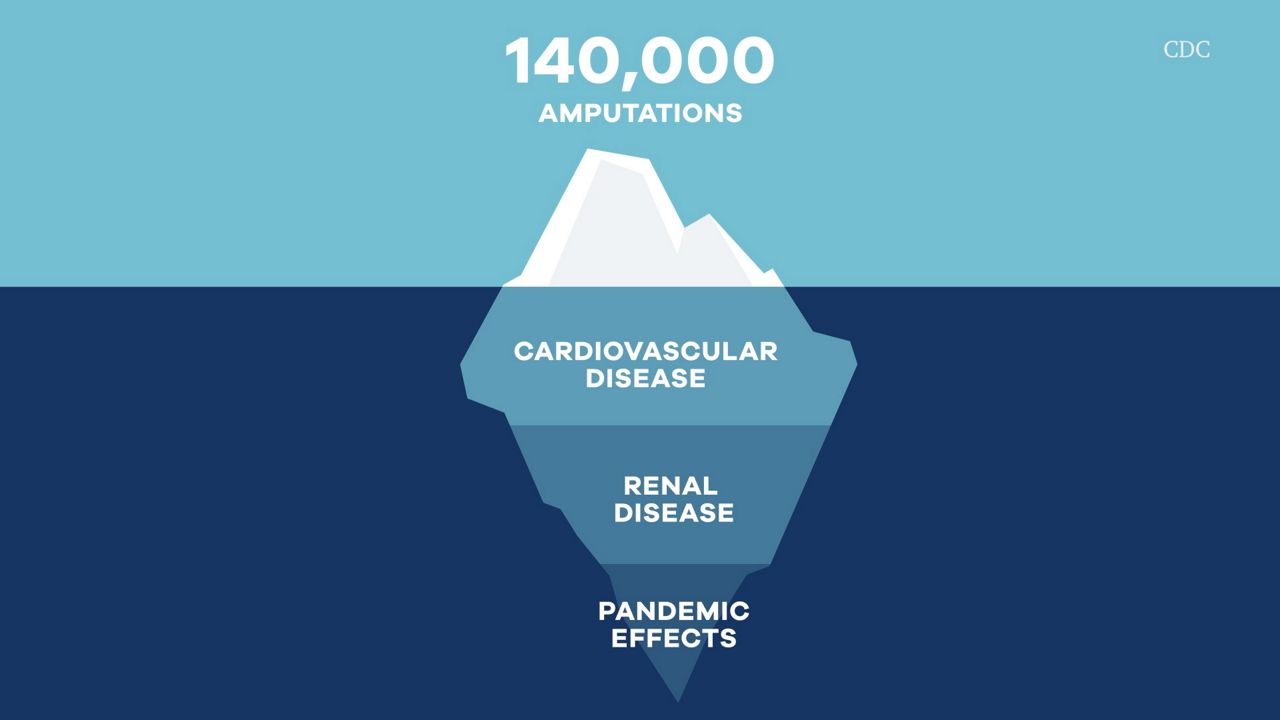

The scale of the problem is vast. There are an estimated 140,000 diabetes-related amputations each year in the U.S.

Amputations are just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to the type 2 diabetes crisis. Equally devastating are its less visible effects. About a third of diabetics also have cardiovascular disease. As of 2018, more than 300,000 Americans were living with end stage renal disease because of uncontrolled diabetes — requiring dialysis treatment or a kidney transplant.

The pandemic has only made matters worse. For a time it was harder to get healthy food, exercise, and even make it to medical appointments. Diabetics were also at a much higher risk of serious COVID-19 illness.

“Last year, the death rate in diabetics rose by 15% because of COVID,” Fakorede says.

Otha Rucker was diagnosed with diabetes 30 years ago. Despite changing his diet and losing weight over the years, he knows he’s at greater risk. He says the pandemic was a frightening time, made worse by the discovery that he was suffering from PAD.

Earlier in the pandemic, Rucker began noticing pain and weakness in his left leg — it was always cold. He’d developed an infection around his toenail and one doctor had told him he might need an amputation.

“[The doctor] couldn't get the foot, to do what it normally do, like keep it from getting dark, keep it from losing my leg,” recalls Rucker.

His cousin suggested he visit Fakorede for a second opinion.

“He said, ‘Mr. Rucker, we're going to try to save it. Don't let nobody do anything to it. We going to probably save it,’” Rucker remembers.

The solution was a procedure called an angiogram, which reopens blocked arteries.

“You can take a wire and a balloon and you go and basically, you mash up that plaque against the wall and restore blood flow,” Fakorede explains. “You're basically plowing away the snow and clearing out the highway and you're restoring traffic.”

Rucker says he noticed a difference immediately following the procedure. “I got done, I feel my leg, I say, ‘Oh, that bad boy warm.’”

Fakorede says an angiogram can reduce the likelihood of amputation by as much as 90%. “Ever since I've been here, I can tell you that the majority of my patients do not end up with a knife applied.”

He says that should have been the case for Mr. Rucker, whose angiogram was successful.

Last summer, Rucker noticed a blister on the toe of his right foot — on his healthier leg. Fakorede had confirmed the leg had adequate blood flow just two weeks before, but not wanting to risk an infection, Rucker sought help from a doctor nearby.

At first, he says, everything was going well. The blister was healing. But a week later, an infection set in. His cousin took him to a nearby hospital, where another doctor told him the toe would need to be amputated.

“She told me, ‘just the toe — outpatient,’” says Rucker. Meaning, he should have been in and out of the hospital the same day. But he woke up in the hospital to find that his leg had been amputated below the knee.

“I was hurt when I woke up, seeing that leg gone,” he remembers.

Fakorede insists the amputation wasn’t necessary, but says he isn’t surprised the leg was removed without consent.

“Seventy percent of patients who have end stage peripheral artery disease, known as critical limb ischemia, are offered an amputation-first strategy, nationally.” The majority of those patients, he says, come from low socioeconomic backgrounds, and are largely Black, Latino, or Native American.

He attributes the disparity to systemic racism within the healthcare field. “There are still some racially biased attitudes that are enshrined in policy,” he says.

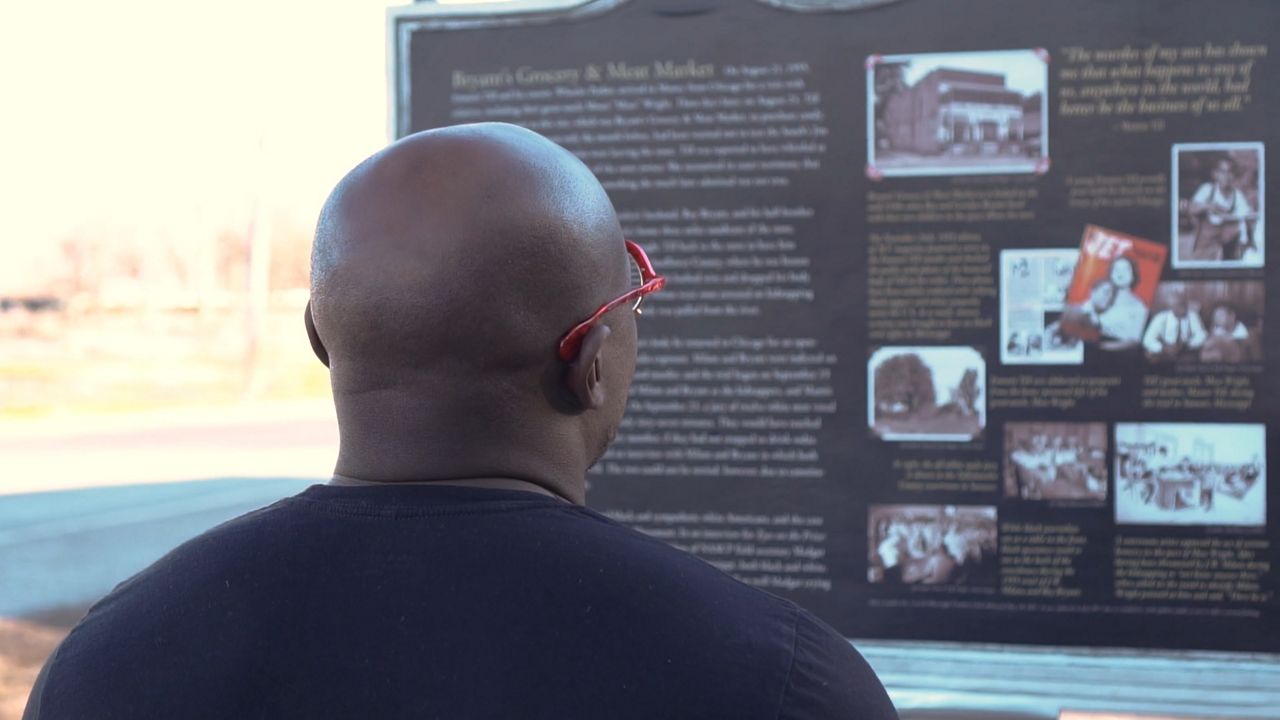

It’s that reality that brought him from New York to the Mississippi Delta. He only planned to stay for a two-month mentorship, but standing in front of a historical site marker on a small back road outside of Cleveland, Mississippi, he found inspiration to stay. He still visits the site often.

“There were Saturdays and Sundays where I'd find myself right here,” Fakorede recalls, pointing to the plaque. It’s a memorial remembering the brutal murder of 14-year-old Emmett Till in 1955.

At the time, his mother’s decision to share the shocking images of his disfigured body became a galvanizing force for the civil rights movement. Fakorede says remembering the activists who came to Mississippi to protest in the wake of that tragedy made him feel that this was where he needed to be.

“Martin Luther King said in 1966 that of all forms of inequality, injustice in health care is the most shocking and inhumane,” says Fakorede. “You don't get to understand that until you look at just the amputation epidemic, particularly in minorities.”

In the South, Fakorede says, racial disparities are on full display — a legacy of past injustices, like the lingering effects of discriminatory housing practice, which placed many minorities far from adequate health care.

“They live in an environment and physical neighborhoods whereby things are debilitated. There are no sidewalks where they can exercise. There are no parks where the kids can go out and play safely, and access to healthy foods are not an option,” he says.

Experts call these realities “the social determinants of health” — a recognition that your income and education levels and where you live are just as important to your health as your genetics.

Little time is spent on these factors during medical training

“There's still a part of medicine whereby your prescription for whatever medical instruction or procedure that's going to be given or prescribed to you, is dependent on a preconceived notion,” explains Fakorede. He calls it statistical discrimination.

The civil rights movement paved the way, he says, to finally tackle this more insidious form of bias. “I should be able to go into a hospital system or health care system and not worry if I'm about to lose my limb because of the color of my skin. That's what ties this movement, the civil rights movement and the health care system together.”

Fakorede hopes that, like with Emmet Till, stories like Rucker’s will draw attention to the current crisis. “Publicize it,” he says, “so the world could see that this has not just happened to Mr. Rucker, it's happening in other states, it's happening in other communities.”

Rucker himself says it has taken time to come to terms with what happened to him. “I woke up many mornings crying.”

“When someone has diabetes, all the fault is on them. But it’s not,” he says. “It wasn’t my fault.”

Rucker doesn’t even know the name of the doctor responsible for his amputation. Now 67, he says his focus is on looking ahead and maintaining his independence.

“I’m going to keep moving forward,” he says. “What’s behind me now, is behind me.”

For more, watch Part 2 and Part 3 of Erin Billups’ and Errol Louis’ joint series on the nationwide diabetes crisis.