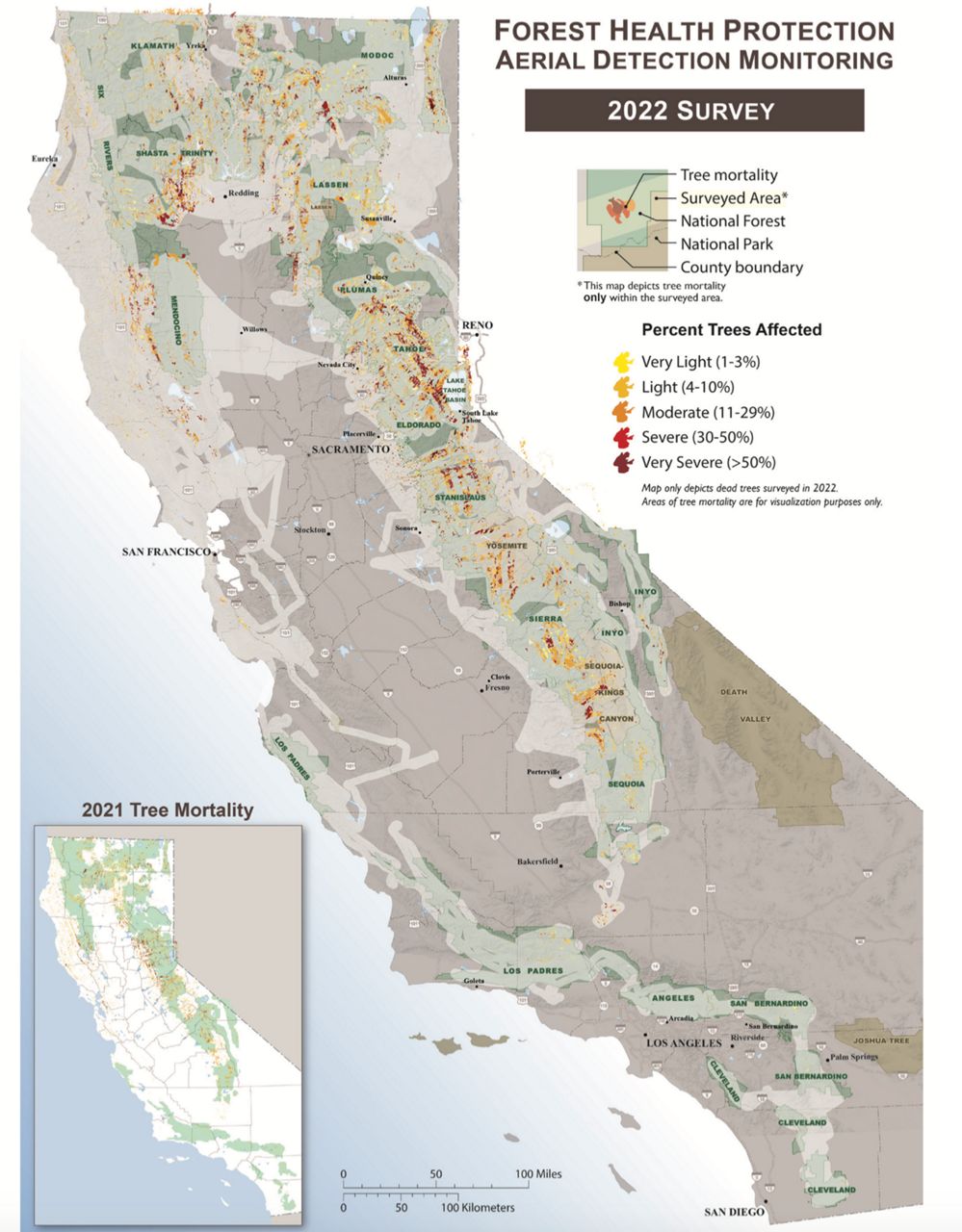

SACRAMENTO, Calif. — Over 36 million trees died in California last year, killing more firs and pines over a significantly larger acreage of the state compared with 2021, according to a new report from the U.S. Forest Service. While the northern, central and eastern parts of the state were most affected, Southern California has been relatively unscathed.

While the survey noted an uptick in deaths of big ponderosa pines in the Big Bear area and a slightly above-normal rate of mortality among white firs, “it’s not huge,” said Jeff Moore, aerial survey program manager for the U.S. Forest Service region that includes California.

Angeles National Forest is seeing an increase in various non-native beetles that can kill oaks and other hardwood trees. They are spreading into southern areas of the forest from private lands, Moore said.

Still, the areas that have experienced the most tree loss in Southern California are in the Palomar Mountain State Park in northern San Diego County and increasingly in San Jacinto in Riverside County.

The Forest Service survey was conducted aerially between July 18 and Oct. 7 last year. Of the 39.6 million acres it measured, 2.6 million acres had experienced tree morality. About 25,000 acres had tree damage other than death.

The species most affected were red, white and Douglas firs, which accounted for 77% of the state’s dead trees last year and were also the largest number ever recorded by the Forest Service since it first began its surveys in the 1970s.

Mortality was especially severe in the central Sierra Nevada range and in the northern interior portion of the state, where multiple species of conifer died because of exceptional drought conditions.

Conducted annually to estimate tree death and damage and get a better understanding of larger mortality trends, the survey for 2022 was conducted following the hottest and driest three-year period in California’s recorded history.

The effects of nine atmospheric rivers that swept through the state between December and January won’t be known until the coming summer, when the Forest Service conducts its next aerial survey.

“If we continue to get good rains and even if it rains some, we could certainly use it,” Moore said. “We need three years in a row of decent precipitation for trees to get back to their full vigor.”