LOS ANGELES — One of the most pernicious aspects of climate change is that its main chemical contributor is invisible.

Whether it’s generated from coal-burning power plants or gas-burning cars, carbon dioxide is difficult to detect. Yet understanding where it’s coming from and how much of it is swirling around in the atmosphere has widespread implications for human health, so researchers at the USC Dornsife school are setting up CO2 sensors around the city to keep tabs.

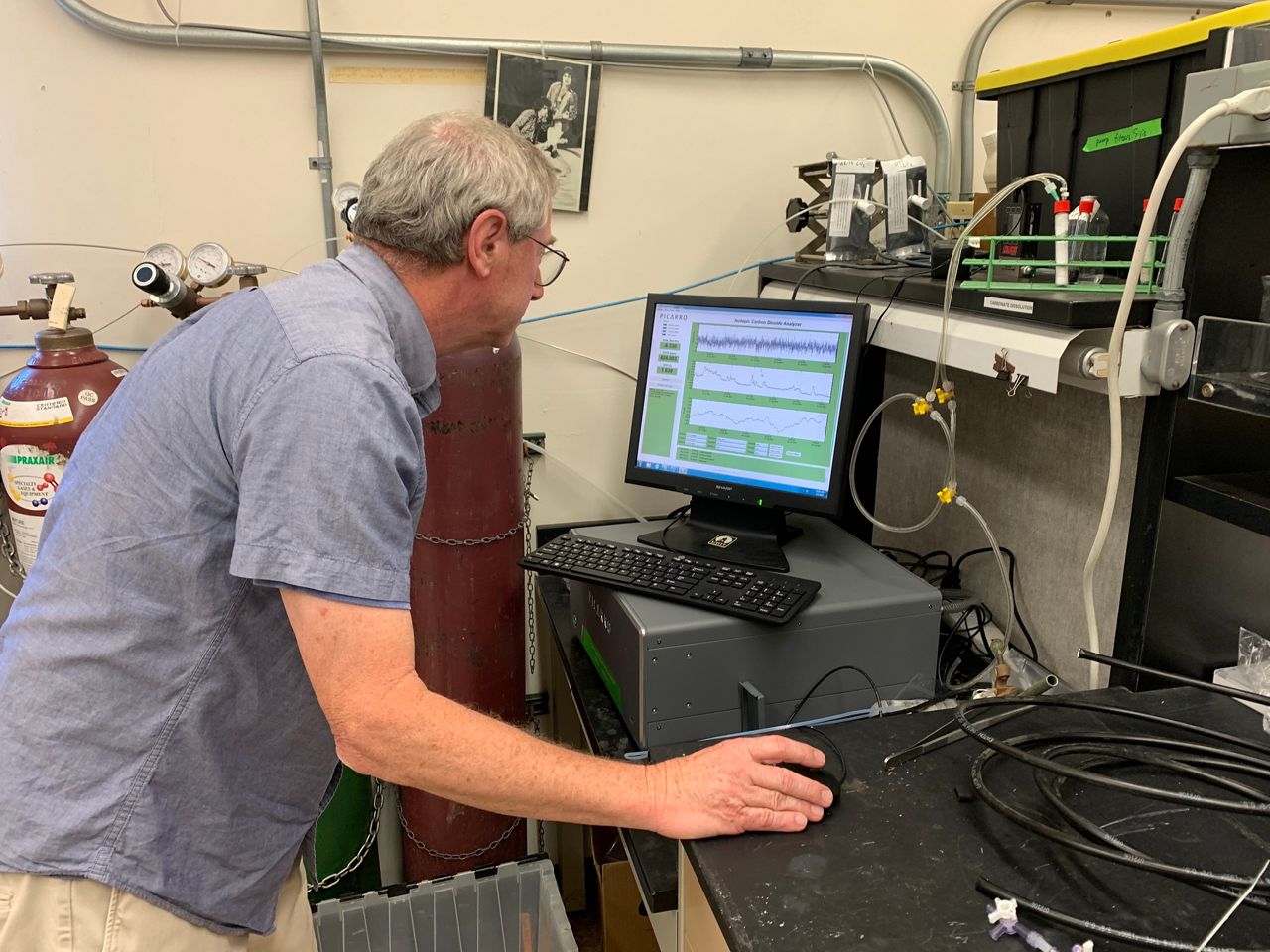

"The big question is, why are carbon dioxide levels high when they’re high, and why are they low when they’re low," said William Berelson, a professor of earth sciences and environmental studies at the USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences who is leading the research. "That’s the big picture of what we’re after."

This summer, Berelson and his team are installing a dozen sensors on the rooftops of Los Angeles Unified School District campuses as part of something called the Carbon Census Network. Stretching along both sides of Interstate 10 from the Beverlywood neighborhood on the city’s west side to communities in East LA, the sensor network is designed to provide a better understanding of how carbon dioxide levels are affected by vegetation, varying topography and on-shore wind flow from the Pacific Ocean.

The work is part of LA’s Urban Trees Initiative, which calls for increasing the tree canopy in parts of the city that are low-income heat zones and could be cooled with strategically planted foliage. As one of the initiative’s principal investigators, Berelson’s task is to help determine the value of trees in the urban setting for improving quality of life and cooling the environment, as well as how trees can act as pollutant sponges.

In addition to carbon dioxide, the sensors that will make up the Carbon Census Network will also measure particulate matter, ozone, nitrous oxide and other air pollutants.

“If trees can remove pollutants, how effective are they? And if they are effective, do certain trees do it better than others?” said Berelson, adding that his research will help LA decide where and what trees to plant to improve air quality. “Being able to inform the city with data as opposed to just planting whatever tree people want wherever they want them, we’re trying to come up with a more systematic data-driven approach to where trees could benefit society the most.”

Trees that are able to trap particulate pollution might not be the same trees that provide cooling shade, Berelson added.

The Carbon Census Network is designed to fill in the gaps of the Megacities Carbon Project, a carbon dioxide monitoring system the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory is also conducting in the LA area with sensors spread out from Fullerton to Compton to Pasadena and South LA — including the USC campus.

The Carbon Census Network sensors will be spaced more closely and can provide neighborhood-level air pollution readings that are more specific than the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s Air Quality Index for LA, which uses readings that are spread out over a wide geographical area.

Because the network’s 12 sensors are situated on LAUSD campuses, Berelson is hopeful the carbon dioxide readings they provide could be useful to individual schools. If a sensor shows air quality is poor, for example, school officials could then hold recess indoors.

“During last year’s fires, air quality was bad throughout the city, but it was also patchy,” Berelson said. “Knowing what is in your neighborhood is really going to help inform decisions.”