TUSTIN, Calif. — Gregory Franklin keeps a photo on his computer, a reminder of the work ahead and the price already paid.

As billions in federal and state dollars stream into school districts nationwide, the outgoing superintendent for the Tustin Unified School District has had many problems to consider.

The photo recalls one such challenge to educators, one of many they're trying to solve and at a scale they’ve never encountered.

The scene is simple: a boy with a baby draped over one shoulder and a toddler off to the side. A snapshot of the responsibilities some of the nation's young students have carried.

“He should be learning,” Franklin said.

But the boy, like some other children, found himself in a position where learning wasn’t the first and final task, but one of many, and not necessarily the most pressing. The COVID-19 pandemic forced him to interweave child care with the demands of a full-time academic schedule.

Educators like Franklin have been figuring out how to help him, and now they’re getting more money to do so.

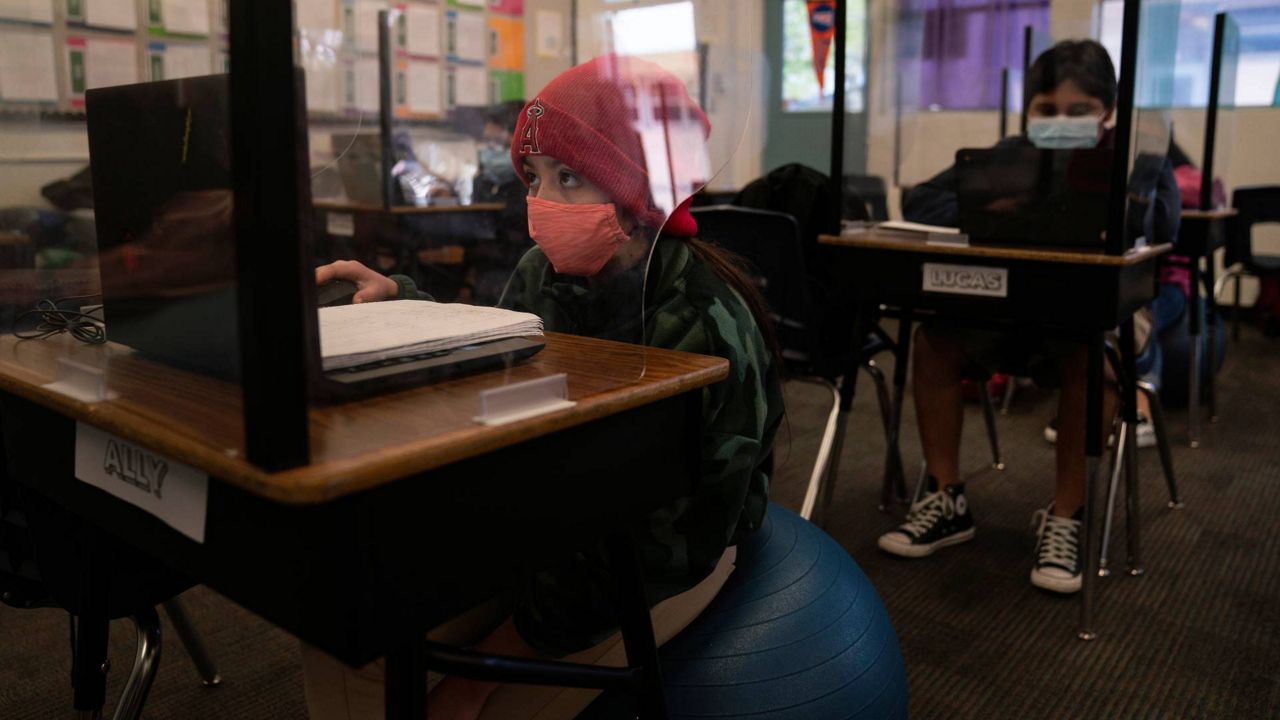

The Tustin school district has already implemented changes, with more to come. So far, they’ve improved, like many schools, access to handwashing stations, increased plexiglass installations, and installed better air filtration into all classrooms and office spaces. They are changes that aim to stave off COVID-19 infection rates well enough to keep students in school.

To attack the learning losses, the district opened up summer school in 2021 to all students, not just those deemed most in need of it. Schools doubled the length of the session, and interested students tripled the number of participants over the prior summer.

Franklin noted that the system to improve and fix learning losses is there, but the challenge is doing it quickly. While the aid money — which amounts to about $70 million for Franklin’s schools — is great, he said it has to be spent by 2023.

“Everybody I know who’s a superintendent wishes we could spread it out over more years,” he said. “While we’ll make great strides in two years we won’t have caught everybody up.”

A key consideration is how to get students caught up without missing out on current material. And how to do that may be complicated by staff shortages. Franklin’s schools have about 30 to 50 open positions, he said, covering cafeteria workers to subject teachers. The most difficult position to fill has been qualified special education teachers.

Added are unprecedented increases in mental health concerns.

Franklin’s district put in place a team with the capability to move quickly back during the great recession. Called The First Team, they're like first responders but for mental health. Now, schools around California are coming to grips with the mental health challenges students have faced at home, and complications associated with returning to the classroom.

Sometimes teachers take students aside — it depends on their individual style — but often, they begin the lesson in a circle with all students encouraged to expound on how they’re feeling.

While the American Rescue Plan has helped schools to get money, they don’t all have the same problems and won’t all have the same solutions. It’s also not the only money they’ll get.

“The big money that will really change stuff is in the infrastructure bill for broadband because that’s how a lot of learning is going to be done,” said Alan Arkatov, a USC professor who has served on the California State Board of Education. “If you have great content and you can’t get it out so a lot of kids can access it, then is it good content?”

COVID-19 remains a major question for all school districts heading forward, as unknowns around booster shots and indoor mask mandates continuously circulate. As variants continue to pop up, solutions for how to confront them are still developing.

How the solutions are rolled out, like online learning and additional supplementary programs, will be an ongoing exploration.

“We’re dealing with more issues than we ever had in the history of education,” Arkatov said.