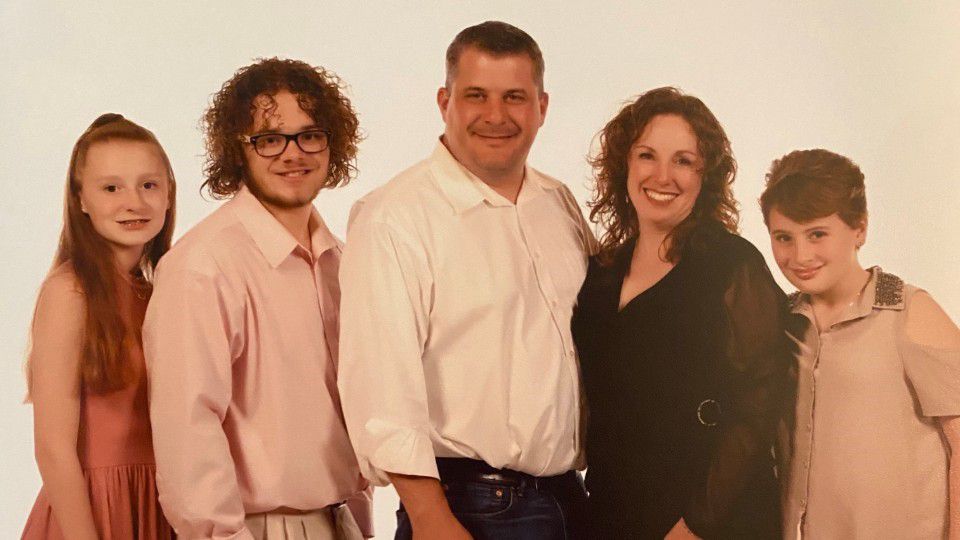

ARLINGTON, TX — Jenny Kocher’s 13-year-old daughter has been struggling with isolation. Last spring, when the COVID-19 pandemic forced her local school district in Arlington, Texas, to transition to remote learning for the rest of the year, Kocher said her youngest daughter’s mental health plummeted.

The soon-to-be eighth-grader has dyslexia, so studying from home was especially hard for her. Both Jenny and her husband Kevin work full-time in the luxury watch repair business – a job they can’t do remotely.

Now, after a summer of on-again, off-again quarantining in Texas, the Kochers are being asked to make the same impossible decision as countless other parents around the country: Do we send our kids back to school and risk exposing them to COVID-19?

“It’s scary to think about them going back to school, but at the same time, I feel like we don’t really have a choice,” Jenny said. “I’d be making a choice between her mental health and my convenience – and the COVID-19.”

After Gov. Abbott announced last month that Texas schools would be reopening in the fall, local school districts have been scrambling to figure out how to anticipate the challenges of new safety protocols and myriad other issues. So far, only Texas and Florida have announced that on-campus learning will be a mandatory option. Arlington ISD, like so many around the country, is offering parents both distance-learning and on-campus choices for their kids – though many economically disadvantaged parents, especially ones with younger children, don’t have the luxury of that choice if they also hope to hold onto a job.

For countless low-income families, school is the only place kids are certain to have access to food, basic medical care, mental health services, and an internet connection. Fort Worth Independent School District school board trustee Ashley Paz, who is still wrestling with whether to send her daughter to school, said that for some students, missing school could have profound long-term effects.

“There are single-parent households where parents are working and aren’t in the home,” she said. “There are food-insecure households; and there are kids who need to be at school. It’s almost an impossible decision. It’s impossible to say what to do.”

As COVID-19 numbers surge across the country, federal and state politicians are leaning heavily on school districts to reopen. In the face of the worst economic crisis in nearly a century, President Trump and other national political figures see the reopening of schools as a critical step in getting people back to work. The administration has threatened to withhold federal funds to states that don’t reopen schools.

“We’re very much going to put pressure on governors and everybody else to open the schools, to get them open,” Mr. Trump said at a forum at the White House. “It’s very important. It’s very important for our country. It’s very important for the well-being of the student and the parents. So we’re going to be putting a lot of pressure on: Open your schools in the fall.”

On a local level, there is a growing sense of uncertainty among parents, educators, staff, and students. In Texas, the school districts are waiting for guidance on reopening from the Texas Education Agency, which is taking its cues from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Educators complain that new guidelines and information arrive too slowly and can be both vague and unenforceable.

Paz and others feel that the state and national plans for reopening have not included input from teachers. The lack of communication from officials could negatively impact public education for years to come, she said.

“We’re already in a national teacher shortage,” she said. “I feel we are going to lose really good teachers from the profession because they are not being heard. I think this will be the final straw for a lot of people.”

While school districts and states hammer out the logistics of this new education model, Jenny and Kevin Kocher are left to worry about a litany of what-ifs.

“Right now, if anybody has to go on quarantine at work, they have to use their own vacation time to do that, so eventually we’re all going to run out of vacation time,” she said.

“It’s scary to think,” she continued. “Of course we’re going to go on quarantine at some point. My older daughter’s school is huge, about 3,000 kids, so for sure it’s going to happen. She said she knows several friends who have already gotten COVID.”

Sarah De Valdenebro is an academic coordinator who works with advanced students at Carter Riverside High School in Fort Worth, Texas. Her husband, a teacher, also works in the Fort Worth school district. Since both parents are being told they will have to show up for work in four weeks, the family is in a difficult position.

“I have been told that I will have to report to work, but I’m supposed to have a choice about whether or not my daughter reports to the school,” she said. “If I have to report, then she has to report. What if I have a medically fragile child? Then I’m in the position of having to choose between my job and my kid.”

On Tuesday, the Texas Education Agency announced a new set of public safety guidelines for Texas schools. Some of the measures included: mandating that every student more than 10 years old wear a mask; teachers and staff must self-screen for COVID-19 symptoms before going to campuses each day; and that schools "should attempt" to have hand sanitizer or hand-washing stations at each entrance and are encouraged to supervise students in hand-washing for at least 20 seconds twice a day.

As districts prepare to implement the new guidelines, TEA staffers will be working from home for the foreseeable future.

Hao Tran, a science teacher at Trimble Tech High School in Fort Worth, Texas, said she felt disappointed by the TEA guidelines.

“Requiring PPE for all students and staff is unrealistic,” she said. “Expecting a 10-year-old to wear a mask all day long is unrealistic. Expecting to clean classrooms between classes is unrealistic. The plan we have now is not going to work, but I don’t know what would work.”

What the guidelines didn’t say is what is bothering De Valdenebro and many others. She has reached out to the Fort Worth ISD for clarification on some issues, but she has yet to hear back.

“My main concern is that we have zero information about how the quarantine process will proceed,” she said. “As we know, we all go back and someone will test positive almost daily. What does that quarantine process look like? More specifically, how is that going to affect our sick days and our time out of work? Am I going to have to prove that this person was positive? My husband is an in-class teacher at a Fort Worth school, so what if he’s exposed? Do I then have to quarantine as well? Is that going to be covered?”

The Fort Worth school district’s superintendent, Dr. Kent Paredes Scribner, said in an email that the district is committed to following the safety protocols established by federal, state, and local authorities. As of July 9, he said, the district has enrolled 11,804 students for virtual learning and is on course for 43 percent of students to study from home.

De Valdenebro – and every other educator interviewed for this story – said she is not satisfied with the current safety precautions.

“I don’t consider myself to be high-risk, but considering the average age of individuals who work in schools is typically older, certainly with substitutes, it’s risky,” she said. “The thing that we always have to do when we’re short on subs is we combine classes. That’s the opposite of what can reasonably do right now.”

Last spring, schools around the country received a crash-course in virtual learning. When the COVID-19 shutdown hit, school districts across the U.S. distributed electronic devices, set up free internet hotspots, passed out free meals to students and parents, and provided other supplies. To many, the ordeal felt like an academic scramble drill.

This school year in Fort Worth, the district has been working all summer to fine-tune its remote learning.

“Doing the virtual school online was difficult for us, even with both my husband I working from home and being able to sit and help our daughter,” Paz said. “And we’re in a very privileged position to be able to do that.

“This coming school year, the virtual school will be very different,” she continued. “It will be much more inclusive than it was last spring because they’re not throwing it together last minute.”

Compounding the frustration of teachers is the looming specter of standardized testing. Last year, the national Education Department granted waivers from federal mandates, like standardized testing. Georgia was the first state to request a waiver for the 2020-21 school year, but Texas hasn’t followed its lead.

“That adds an additional layer of pressure that no one needs right now,” she said. “Of course, we need to be able to measure how our students are performing, but we have other ways to do that.”

For Tran, last year’s remote school was stressful for reasons besides academics.

“Kids were lost,” she said. “Kids were probably not eating. Kids didn’t know how to adapt to emotional isolation. A few of them were admitted to the hospital for suicidal thoughts.

“It’s tragic, and you worry about them like they’re your own kids,” she continued. “You worry what their lives are like. A student emailed me and said, ‘I can’t get to your work today. I promise I’ll do it,’ because she was working. Their parents were furloughed or laid off. Now the child has become the breadwinner in the family. It broke my heart.”

De Valdenebro and others believe the process of reopening schools during a pandemic feels rushed again. Various education groups around the country have requested more funding to accommodate the last-minute panic to reopen, but those requests are stalled in Congress. During a recent conference call with governors, U.S. Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos said that of the $13.5 billion allocated to school districts through the federal coronavirus rescue bill, only 1.5 percent, or $195 million, had been used by the states.

“So everybody has been waiting to see, and now we’re at a point where it will have to be rushed,” De Valdenebro said. “Knowing what I know about public health, and looking at the trajectory of cases in Texas, there’s no way that any reasonable person who interprets data accurately could say that it is wise to take 30,000 students and put them in school.”