ORANGE COUNTY, Calif. — White House plans to send four rapid tests to every household have awakened critics who wonder if those tests are reliable enough to slow a winter coronavirus spike.

For University of Massachusetts, Amherst immunologist Andrew Lover, it’s the best bad strategy available.

“If people literally have no access to testing, then a not great home test is still a test,” Lover said. “We’re in a bit of a bind because ideally, we would have built some really massive scale infrastructure 18 months ago. But now we’re at a point where it’s hard to make the case to build those facilities for testing.”

COVID-19 has endured as a public health crisis and a key battleground for political sparring among elected officials. Hundreds of billions in federal dollars have flowed to all corners of the problem. Schools have received money to target learning losses and teacher shortages. More vaccines have been bankrolled along with the purchase of dosages to be distributed to foreign countries of lesser means. And more doses, boosters and vaccines are continuously in the works even as the Food and Drug Administration is still vetting the drugs already in use.

A continuing challenge has been to get Americans to receive the vaccine and boosters, and to properly social distance or quarantine.

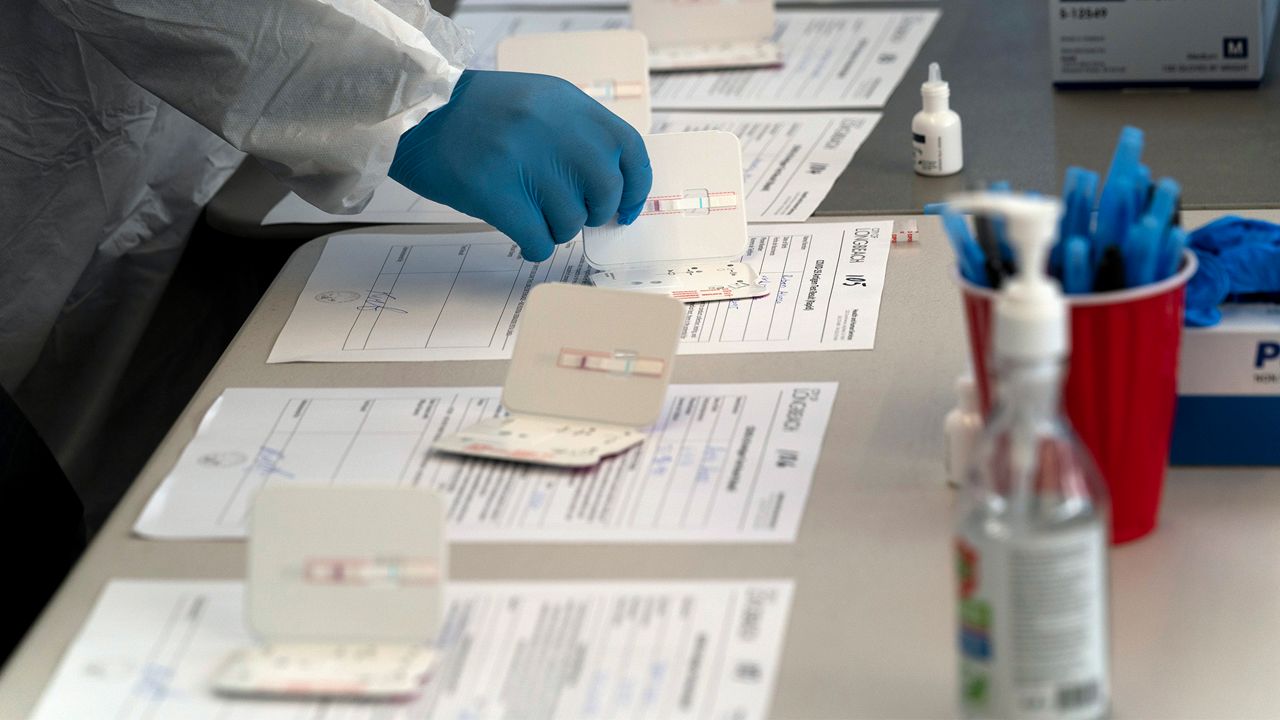

Testing, and access to it, has been another hallmark challenge of the past two years.

Orange County has struggled to funnel people to its testing site at the Orange County Fairgrounds in Costa Mesa. While numbers in the county have dipped in recent days, the overwhelming surge bolstered by the omicron variant has inflamed concern.

But as the pandemic endures, Lover said the political will to sink vast amounts of additional dollars into infrastructure to allow for high volumes of the more effective PRC tests is a tough sell.

Even if the case was successfully made, steering people to those test sites might be too much to ask.

“You’ve got to make the healthy choice falling-off-a-log easy and still some people won’t take it up,” Lover said.

Delivering these tests directly to households is one way to make it easier.

“There’s not refrigeration requirements here. From that standpoint, it’s just like any other package,” said Hani S. Mahmassani, a professor of logistics at Northwestern University.

The challenge, Mahmassani said, is more about the production of the test. If that’s squared away, delivery won’t be a problem. But severe shortages leading to purchasing quotas at major chains like Walgreens indicate retailers’ problems meeting demand.

Many Americans may not even know that free tests are available. Lover said it might be a better strategy to stock public spaces like restaurants and shopping malls with tests to create the kind of visibility Americans might need to actually obtain the tests.

Another key problem, Lover said, comes down to the number of tests. Four tests per household won’t cut it. Earlier versions of rapid tests came in pairs with instructions to take one test then the second eight hours later. That, Lover said, can make up for the relative ineffectiveness of the tests and offer some small measure of additional reliability

The bigger difficulty is persuading busy Americans to seek out the tests online, enter mailing information, then actually use them when they arrive.

Testing positive for the coronavirus looks different depending on what kind of job and benefits workers might have. Some companies have set aside special sick leave for employees who test positive for COVID-19. Others haven’t. Workers in the service industry may have to find extra days off to work through illness. Others might not disclose their illness and head to work anyway.

“I think for all the people who have higher risk jobs it can be really difficult for them to take time off work to go and get a swab done,” Lover said.

The result, likely, will be continued spikes in cases each winter as new variants arrive on the heels of flu season.

“We’ve really painted ourselves into a corner,” Lover said.