CALIFORNIA — More than a year has passed since COVID-19 first arrived in California, and politicians are still grappling with how to allay peoples' fears and mistrust.

In the pandemic's chaotic early days, public officials contended with how to translate health advice into real, safety-first policies.

Masks were the question of the day. Health officials first downplayed the need for masks, anticipating a supply crunch. The Los Angeles Times published an opinion article titled "Your hoarding could cost me my life — a doctor's view from the coronavirus front lines."

Then masks became a necessity, officials said, to slow the spread of the virus and protect the country's most vulnerable citizens.

Then came discussions of a mask mandate requiring all citizens in public to wear a mask.

Dr. Nicole Quick, the Orange County chief health officer, was the first casualty of the mask mandate outrage. The county contains some of the most outspoken anti-mask cities in the state. Huntington Beach City Councilmember Tito Ortiz famously eschews mask requirements. He recorded a video of himself on social media leaving a burger restaurant in protest that required mask-wearing.

Quick had pushed ahead with a mask mandate early on only to step down in June of last year once outrage grew loud enough.

"She thought she was probably following the order from the state," said Andrew Do, chairman of the Orange County Board of Supervisors.

The outrage, Do said, consisted of a complex mixture of mistrust and feelings of helplessness brought on by pandemic-related restrictions.

And trust in public officials has been ruptured.

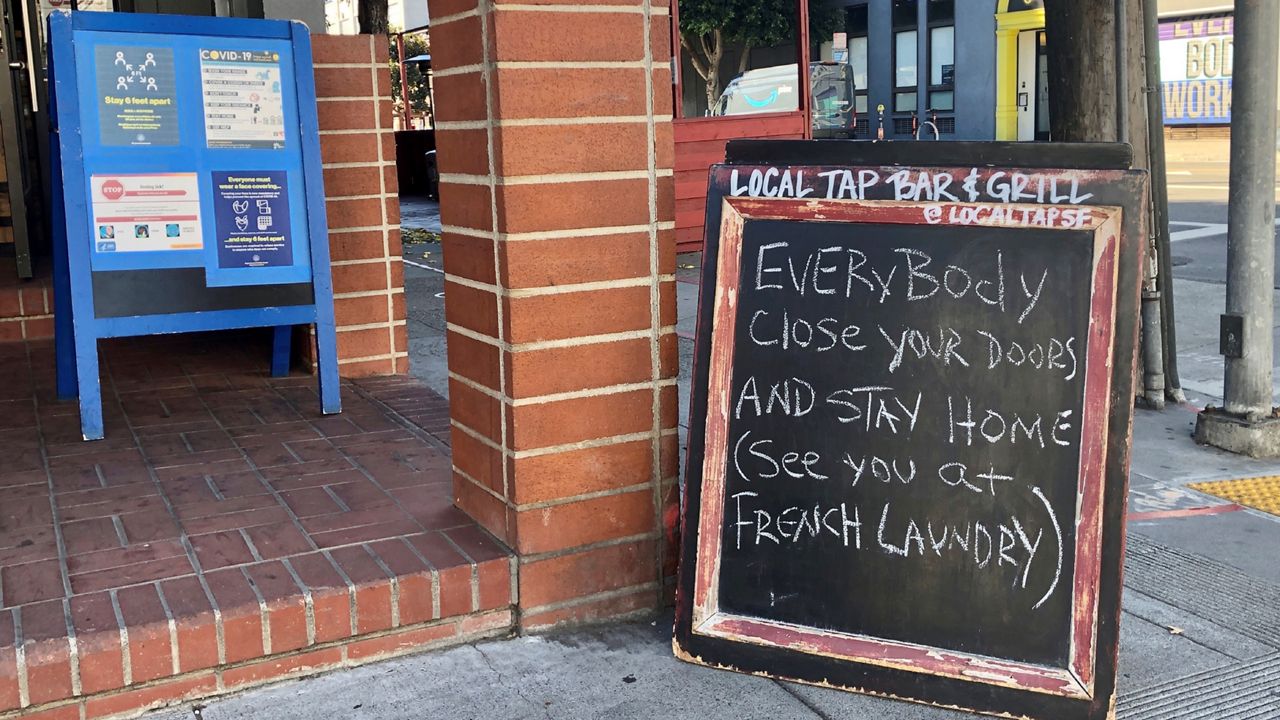

Former President Donald Trump had taken to the airwaves to suggest inhaling cleaning products to cleanse the lungs of any trace of the virus. Gov. Gavin Newsom, after he had approved a shutdown, was eyeballed at the three Michelin star French Laundry during a dinner party. And even after the upswell in anger over Newsom's gaff, Los Angeles County Supervisor Sheila Kuehl was seen dining out after approving a shutdown on in-person dining.

"Government is only as effective as the respect people have for that government," Do said.

Mixed messages, shutdowns, job losses, and a building backlog of unpaid rents kept steady tension on people.

The hope all along has been that a vaccine would arrive to get America back to work, school, and life as normal. Health officials are still cagey about what "normal" means and when masks can be permanently retired. President Joe Biden is pushing to get out enough vaccine doses for every adult in the country by the start of the summer.

Mark Keppler, executive director of the Maddy Institute at Cal State University, Fresno, said politics is all about timing.

"Economic forecasters at UCLA, for example, are predicting that California will have a robust economic rebound coming out of the pandemic, and it will happen before the rest of the nation," he wrote in an email. "If in-person instruction is back by the Fall, it is likely that the past year will be quickly forgotten by most."

For politicians, the pandemic has presented a range of administrative, budgeting, and communication challenges. But Keppler called the coronavirus outbreak a "once-in-a-generation opportunity to show leadership."

The recall effort for Newsom, which has gained significant momentum, has shown a lack of faith, among some voters, in his leadership. But California has not fared the worst in the nation. While its coronavirus case numbers are the highest, they're middle-of-the-road by a per-capita count. While the budget looked like it may be in crisis, tax revenues did not take as heavy a beating as expected.

"No one expects perfection," Keppler wrote. "The problem occurs when a nation (or) state… is doing demonstrably worse. In that case, a leader's actions or inactions have consequences. No one wants to hire a coach with a losing record."

Depending on who you ask, Orange County's record has been mixed. When restaurants were ordered to close in-person dining, some around the county, including Huntington Beach and Newport Beach, chose not to. Some as a form of protest, but many out of necessity. The county has implemented a massive rent protection program buoyed by federal money, and some cities have supplemented these programs with their own funds.

Do said much of the friction from the pandemic could fall away as circumstances improve.

"So much was outside of our control that there was a sense of helplessness," he said. "At our core, I think we are still a community of people."