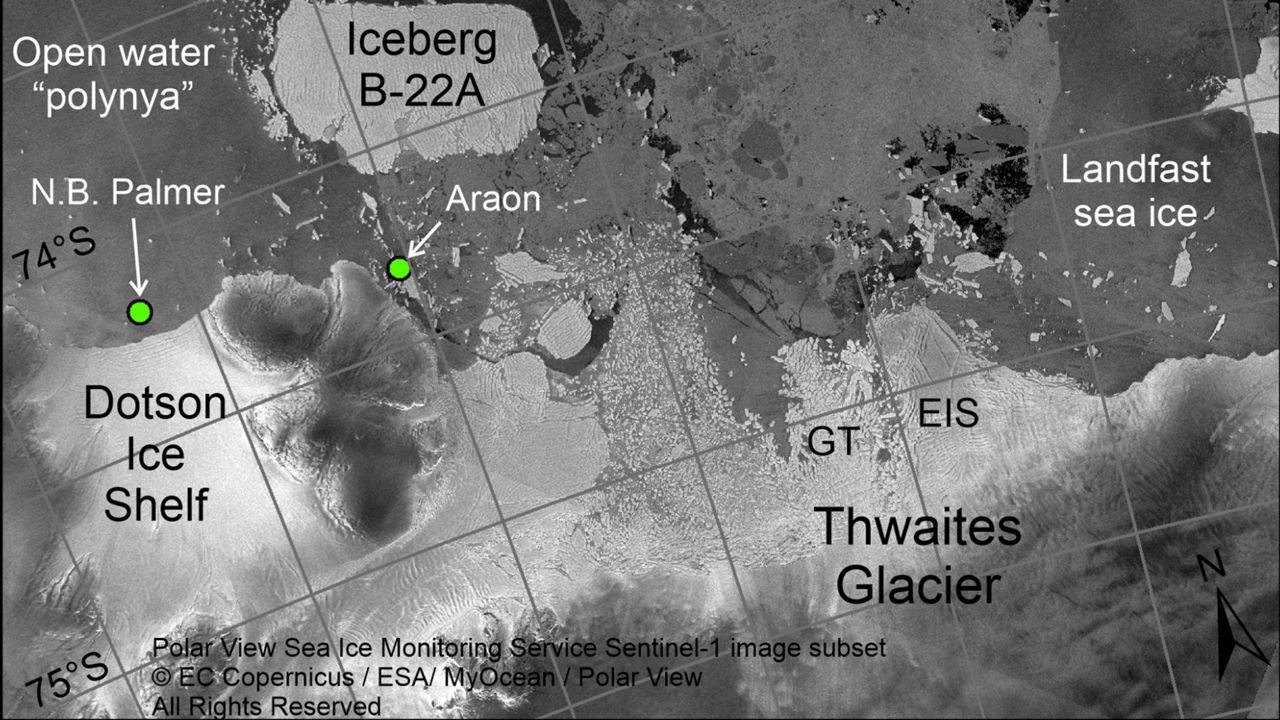

In October, the nonprofit group Climate Central released a collection of images showing what long-term sea level rise might look like if no action is taken to address climate change.

The pictures were almost apocalyptic.

What You Need To Know

- Knowing urban areas have been responsible for the bulk of greenhouse gas emissions but also that cities can be a big part of the solution, climate change is at the forefront of city planners' minds

- There are a number of ways city planners are simultaneously working to slash emissions and preparing for a future where sea level is higher, tropical storms are more frequent and intense, heat is more extreme, droughts are more prevalent and wildfires continue to threaten homes and businesses

- They include determining whether or not to build in potentially vulnerable areas, setting requirements so that buildings are greener but also better withstand weather events or wildfires and designing cities in a way that encourages more people to take public transportation, bike or walk to work

- While some cities are highly active in bracing for climate change, the reality is many are not, and one planning expert said she’s concerned about a growing gap between big cities, which can devote ample resources to tackling climate change, and smaller ones, some of which might not even employ a full-time planner

Even if the planet’s warming is limited to 2 degrees Celsius over pre-industrial levels, most of lower Manhattan’s streets would resemble rivers, according to the projections. At 4 degrees, the water would reach up to midtown — even farther north along the Hudson and East rivers. The story is the same for other major U.S. cities, Washington, D.C., and San Francisco among them.

And in July, a group of NASA researchers projected that high-tide flooding, in part because of the rising sea level, will be so frequent by the mid-2030s that it will impact almost all U.S. mainland coastlines.

It’s no wonder that in 2021 the changing climate is at the forefront of the minds of city planners. They know that urban areas have been responsible for the bulk of greenhouse gas emissions but also believe that cities can be a big part of the solution.

“Urban planning is critical to climate change mitigation, but then also the majority of climate impacts are really going to be experienced at a local level,” said Sara Meerow, an assistant professor in the School of Geographical Sciences and Urban Planning at Arizona State University.

“These kinds of questions about essentially what gets developed where are at the heart of planning, and those are really, really critical to shaping climate risk. And conversely, there's a lot that can be done at the local level to try and adapt to climate change through new infrastructure, through different kinds of policies and programs to help protect areas from, at this point, inevitable climate impacts.”

There are a number of ways city planners are simultaneously working to slash emissions and preparing for a future where sea level is higher, tropical storms are more frequent and intense, heat is more extreme, droughts are more prevalent and wildfires continue to threaten homes and businesses.

They include determining whether or not to build in potentially vulnerable areas, setting requirements so that buildings are greener but also better withstand weather events or wildfires, creating more greenspace to absorb water and designing cities in a way that encourages more people to take public transportation, bike or walk to work.

“If we want people to drive less, we have to make sure that homes are located closer to workplaces so that people don't have these long commutes or extraordinary commutes,” said Michael Boswell, head of the city and regional planning department at California Polytechnic State University. “So we're trying to reach out in California to achieve what we call 'jobs-housing balance.'

“But also we're trying to provide people alternatives to driving as well," Boswell added. "At least getting people, if they are going to drive, into an electric vehicle and implementing a number of programs to encourage electric vehicle use, like putting in charging stations and things of that nature.”

To try to limit greenhouse gas emissions, many communities in California, for example, have banned natural gas connections on new construction, forcing the structures to be exclusively electric. Meanwhile, in cities such as Morro Bay and San Luis Obispo, where Boswell works, businesses and residents may now get their power from a locally controlled public agency called Central Coast Community Energy that puts an emphasis on supplying more clean and renewable electricity, including wind, solar, hydroelectric and geothermal energy.

“We've done such a good job of cleaning up our energy grid and moving to renewables,” Boswell said.

In South Florida, four counties — Broward, Miami-Dade, Monroe and Palm Beach — were considered trailblazers nearly 12 years ago when they formed the Southeast Florida Regional Climate Change Compact.

The counties collaborate to reduce regional greenhouse gas emissions, implement adaptation strategies and build climate resilience.

Jim Murley, chief resiliency officer for Miami-Dade County, said the counties recognized that together they’d have a louder voice when pursuing climate-focused legislation in the state and national capitals.

“We found that it made a lot more sense to be in a collaborative effort, voluntary effort of the four counties, and to make the impact greater in trying to turn around that perspectives in Tallahassee and in Washington,” he said.

Solving anticipated problems related to climate change starts with understanding the problems. A key aspect of the Compact, knowing it can’t rely on data from the past to predict the future, was assembling a panel of experts, including scientists and federal officials, to create a unified projection for sea level rise that informs planning decisions made by the four counties.

New York City has something similar, called the New York City Panel on Climate Change.

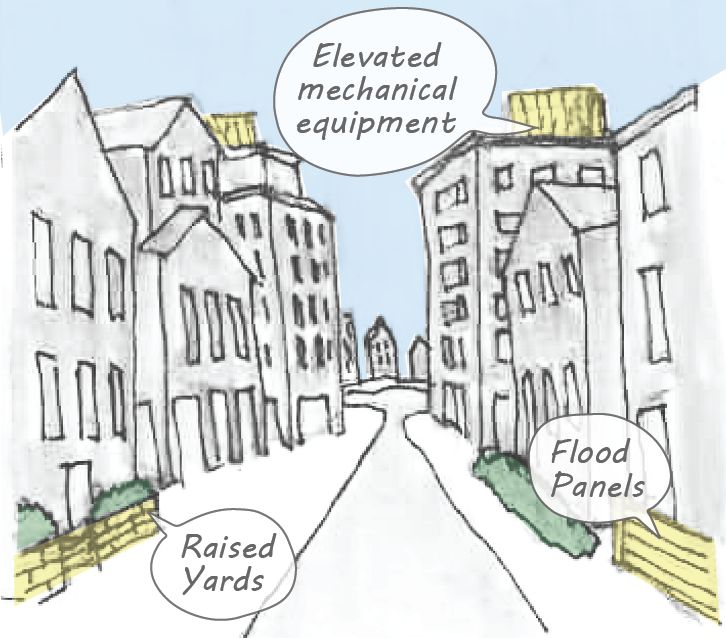

In May, New York adopted a package of rules called “Zoning for Coastal Flood Resiliency” that makes it easier for owners of properties in the floodplain to retrofit buildings to protect them. Those changes include allowing for buildings to be elevated and for important mechanical, electrical and plumbing equipment to be relocated to higher ground.

Michael Marrella, director of waterfront and open space planning at the New York City Department of Planning, said Superstorm Sandy in 2012 exposed the need for better designed homes in the city’s coastal areas.

“It was the distinction between homes being torn off their foundations and undermined by coastal erosion versus other homes that were able to be reoccupied within a matter of days,” he said.

Marrella said he doesn’t anticipate many property owners using the new zoning rules to proactively invest in making them more resilient but that it will now be easier to rebuild smarter following the next storm, much like some did following Sandy.

Experts say planners in many coastal cities will inevitably have to make the unfortunate decision that some communities cannot be saved and begin a process called “managed retreat” away from high-risk areas.

“We're going to have to work to try and figure out which places we will adapt and protect,” Meerow said. “Where will we elevate versus where will we move away from, where will we retreat from?”

Retreating could mean voluntary government buyouts of properties. Such buyouts have been offered following Sandy in New York and New Jersey and other recent hurricanes in Louisiana, but with the prospect of large swaths of coastlines growing more prone to flooding in the coming decades, the pricetag for buyouts could prove to be astronomical.

New York took a baby step toward managed retreat in 2017 when it designated four coastal areas that are “at exceptional risk from flooding and may face greater risk in the future” as “special coastal risk districts.” The designation places limits on new development in those areas and ensures new development follows open space and infrastructure plans.

“In those districts, we very much restrict the opportunity for increased density, recognizing that those neighborhoods are going to face a very uncertain future,” Marrella said. “And so we don't want additional populations at risk in those neighborhoods.”

Meanwhile, some coastal communities are relocating crucial infrastructure, including water treatment plants, further inland. Places such as Miami-Dade County and Phoenix have added new officials tasked with addressing the public health and environmental challenges related to extreme heat. And other places have added or are considering building storm walls as well as artificial barrier islands and breakwaters that disrupt storm surges.

While some cities are highly active in bracing for climate change, the reality is many are not, experts said.

The world is not on track to meet the goal of limiting global warming to 1.5 or 2 degrees, and “the blame goes all the way from the top to the bottom,” Boswell said.

“Simply put, everyone in every level of governance has a role to play, and every part of society has a role to play,” Boswell said. “I wouldn't say that any part of that is doing as much as they need to do. I mean, it's a real climate crisis.”“Simply put, everyone in every level of governance has a role to play, and every part of society has a role to play,” Boswell said. “I wouldn't say that any part of that is doing as much as they need to do. I mean, it's a real climate crisis.”

Meerow said she’s concerned about a growing gap between big cities, which can devote ample resources to tackling climate change, and smaller ones, some of which might not even employ a full-time planner.

“For these communities, developing a whole climate change plan is going to be really challenging,” she said.

She said smaller communities will need federal support to plan for climate change and implement strategies.

The prospect of coastlines shifting inland, shore towns being abandoned, buildings being elevated and seawalls being erected around cities can sound frightening to many. When asked what the future might look like, city planners are cautious not to make any predictions, but they believe much can still be saved and note that the world we live in is constantly evolving.

“If we were to rewind New York City 80 to 100 years, that takes us to the 1920s to the 1940s,” Marrella said. “And yes, New York City looked a lot different back then. I'm looking out my window, and the city would have been a lot lower scale. And in the course of 80 to 100 years, cities change drastically. And so yes, there's the possibility that New York City can change drastically in that time period, with or without the climate risks.

“But I'd like to think that New York City is going to remain an important capital for all things,” he added. “And what that means is that we would be taking proactive steps over the course of the next 80 to 100 years to address those risks. And I think you're seeing that now with the planning that the city has done.”

Murley noted that South Florida was once swampland that was built up and engineered to to be livable for now millions of people, in large part by constantly pumping out water.

“We have some of the smartest people who have been doing it, and they're smart enough to change,” he said. “And they will, and our system will adapt, and 50 years from now, we won't look the same way.”

Note: This article was updated to correct the spelling of Michael Marrella's last name.

Ryan Chatelain - Digital Media Producer

Ryan Chatelain is a national news digital content producer for Spectrum News and is based in New York City. He has previously covered both news and sports for WFAN Sports Radio, CBS New York, Newsday, amNewYork and The Courier in his home state of Louisiana.

)